A Place of Refuge

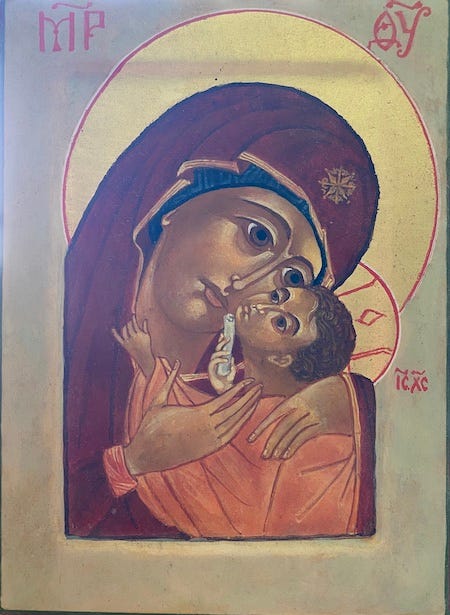

Praying with the icon of Our Lady of Korsun.

The original version of the icon known as Our Lady of Korsun is believed to have been painted by Saint Luke in Ephesus in the first century AD. A copy made its way to Korsun, the Slavic name for the Byzantine holding of Cherson on the Crimean Peninsula. In the late tenth century, the Great Prince Vladimir brought this copy to Kiev, the capital city of Kievan Rus’, where it came to be known as the “Korsun icon.” Vladimir had been baptized in the Black Sea off the coast of Korsun, so the icon’s provenance had personal significance. There was an element of political symbolism, too, as he used the transfer to mark the Kievan state’s adoption of Christianity in 988.

Our Lady of Korsun is an example of an Eleusa or “tenderness” icon, a Marian motif that depicts the Christ Child pressed to his mother’s cheek. In the Korsun icon, the faces nested together are given an added visual detail: a small scroll Christ’s right hand lifts to Mary’s lips, representing the gospel he comes in time to deliver. Their gazes meet each other mediated by this word of God. They express in a silent look the love that is the kernel of that word, the message at the heart of the text rolled up and proffered as a gift.

Praying with this icon, I think often of biblical images of “tasting” the word that begin with the petition of Psalm 51:

O Lord, open my lips, and my mouth shall declare your praise.

Then moving to the masticatory imagery of the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel:

Your words were found, and I ate them, and your words became to me a joy and the delight of my heart; for I am called by your name, O Lord, God of hosts. (Jer 15:15)

I opened my mouth and he gave me the scroll to eat. Son of man, he then said to me, feed your belly and fill your stomach with this scroll I am giving you. I ate it, and it was sweet as honey in my mouth. (Ezek 3:2-3)

And onward to the book of Revelation:

So I went up to the angel and told him to give me the small scroll. He said to me, “Take and swallow it. It will turn your stomach sour, but in your mouth it will taste as sweet as honey.” (Rev 10:9)

The passage from Jeremiah reappears every other week as the reading for Monday Lauds in the Benedictine breviary, which regulates reflection on this assimilation of the word from Christ to Mary, and from Mary, through her intercession and example of ultimate receptivity, to us. It is also an occasion to meditate further on the mediatory nature of the gospel—a moment when Christ transfuses himself into written language, “becomes” text, as it were, so that we might experience him in the reencoding of symbol, sound, and scene.

In addition to these verbal underpinnings, there are striking visual cues that stand on their own in the Korsun icon: the hands, for instance, both Mary’s that envelop the Christ Child and her son’s whose fingers twist around the scroll like second sheet of parchment and whose left raises playfully to tug at his mother’s mantle. There is the way that Christ rests against his mother just as the Beloved Disciple will rest against him at the Last Supper, and the intimation of interdependence such a visual parallel implies: at times in our lifecycle we are recipients of refuge, as Christ is here in his mother’s arms; at other times we are called to provide that place of refuge—to develop, as Rowan Williams defines humility, “a capacity to be a place where others find rest.”

The arrangement of the composition reveals a deeper metaphysical architecture: the relationship between being and doing, between the changeless impassability of God and the shifting, provisional nature of our daily acts. Mary looks steadily to Christ as a reminder that if we focus on being—really, on Being itself—the sequential acts of doing will follow. So often we reverse this dynamic; we think that if we just read one more book, give one more hour, go one more mile along the way, we will somehow build our way to Being, as if God were a composite of our tiny efforts and sacrifices. Perhaps, in a sense, God is such composite, multiplied across populations back and forth through time, but trying to structure our spiritual life on such a claim means constantly weighing our actions. For our left hand not to know what our right hand is doing (cf. Matt 6:3), to become joyful givers (cf. 2 Cor 9:7), we can look to Our Lady of Korsun’s expression of patient expectancy and trust that we, too, will receive a word of instruction delivered anew each day.

Michael Centore

Editor, Tomorrow’s American Catholic

Yay ! Congratulations on your 1st Issue of Tomorrow's American Catholic! Unless I missed one !