Breathe Christ Always by Michael Centore

On Nicholas Worssam's "In the Stillness, Waiting: Christian Origins of the Prayer of the Heart"

In the Stillness, Waiting:

Christian Origins of the Prayer of the Heart

By Nicholas Worssam, SSF

Liturgical Press, 2025

$24.95 189 pp.

In his monograph on the Jesus Prayer, the author known pseudonymously as A Monk of the Eastern Church quotes the Russian theologian Nadejda Gorodetzky:

The name of Jesus may become a mystical key to the world, an instrument of the hidden offering of everything and everyone, setting the divine seal on the world. One might perhaps speak here of the priesthood of all believers. In union with our High Priest, we implore the Spirit: Make my prayer into a sacrament.

Nicholas Worssam’s In the Stillness, Waiting: Christian Origins of the Prayer of the Heart might be read as an initiatory text into this “priesthood of all believers”—the state where, in an image drawn from Julia Konstantinovsky’s biography of Evagrius Ponticus, the contemplative mind “is transformed into the ‘true church’ of God, where the cosmic liturgy takes place.” Worssam’s subject is the history, theory, and practice of silence as a spiritual discipline, “a skill to be learned with patient endurance,” and while the Jesus Prayer is at the center of this practice, it encompasses a range of states and aims—dispassion, watchfulness, persistence, perceptiveness, humility—that gather under the central concept of stillness or hesychia.

Citing Kallistos Ware, Worssam establishes the heart as “the primary centre of our human personhood [and] the seat of wisdom and understanding, the place where our moral decisions are made, the inner shrine in which we experience divine grace and the indwelling presence of the Holy Trinity.” The “prayer of the heart,” then, develops along two related tracks: a “watchfulness that guards the mind” and “the descent of the mind into the heart.” For Saint Theophan the Recluse, the nineteenth-century Orthodox bishop known for his writings on prayer, the essence of the practice consisted “in acquiring the habit of keeping the intellect on guard within the heart”—“habit” being an opportune word, given that, as Worssam writes in a chapter on the Desert Mothers, “Cultivating the rule of God in one’s heart needs the persistence of bramble and the patience of an oak.” It is only by habituating ourselves to an awareness of this inward presence—to “Let the remembrance of Jesus be present with your every breath,” as John Climacus instructs—that we can begin to issue the mercy and compassion that are the center of God’s actions. A Monk of the Eastern Church turns this on a pacific metaphor: “The Jesus Prayer must be ‘breathed’ continually,” he writes. “When the intellect has been purified and unified by it, our thoughts swim in it as merry dolphins in a peaceful sea.”

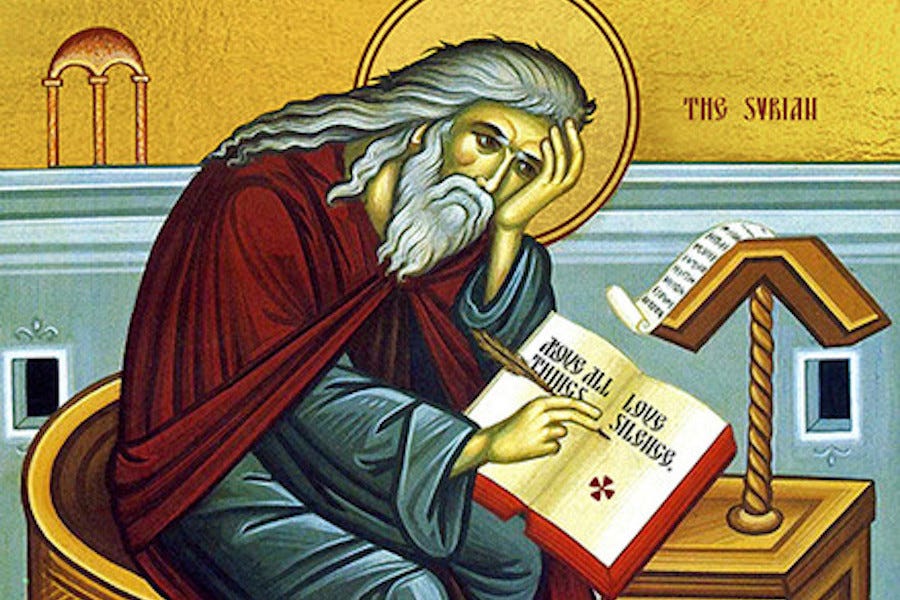

In the Stillness, Waiting introduces us to key figures who shaped and sustained the hesychastic tradition—though “tradition” is a bit of a misnomer, as hesychasm is more of a disposition or way of being than a codified set of practices. In this it differs from more mental, self-reflective techniques such as the Ignatian Examen, which tend to focus on itemizing the individual conscience; hesychasm, instead, applies its energies to realizing that “nothing is achieved by one’s own efforts” and follows the line of limpid simplicity Worssam finds in the fourth-century monk Macarius of Egypt: “All is grace and peace, the work is just in clearing away whatever obscures that grace, to reveal that which has always been present—the radiant goodness of the Lord.” One might even sense a parallel between hesychasm as a mode of prayer and Christianity as a religion, in that both proceed from physical expressions—breath as linked to repetition of the Divine Name in the former, the incarnation of Jesus and the pattern of his life in the latter—rather than a priori ideas or systems. Much as the early Christians spoke of the central tenet of their faith as the “Christ event” and its emerging kerygmatic commitments as “The Way,” so we hear an echo in Worssam’s reading of a teaching of Saint Isaac the Syrian: “Prayer is the way, not the destination.”

With its explication of the spiritual voyage as a threefold path of repentance, purity, and perfection—which connects back to the sixth-century Gazan monk Barsanuphius’s threefold path of rejoicing, prayer, and thanksgiving—and its link between purity of heart and luminosity of spirit, the chapter on Isaac stands out for me as the climax or crescendo of the book. I can think of few saints better equipped to heal the pains of our current age than this seventh-century solitary born in Qatar on the Persian Gulf and briefly bishop of Nineveh or present-day Mosul: the passage from his Ascetical Homilies for which he is most known, and which Worssam quotes here as being “emblematic of his whole spiritual teaching,” glows like a burning coal touched to the lips of Laudato Si’ or Teilhard de Chardin’s evolutionary spirituality:

And what is a merciful heart? It is the heart’s burning for the sake of the entire creation, for people, for birds, for animals, for demons, and for every created thing; and at the recollection and sight of them, the eyes of the merciful pour forth abundant tears. From the strong and vehement mercy that grips their heart and from their great compassion, their heart is humbled and they cannot bear to hear or to see any injury or slight sorrow in creation. . . .

That awareness of the interconnectedness of life, clothed in the mantle of God’s mercy, has what Worssam identifies as “profound effects on the doctrine of the incarnation and the redemption of humankind.” According to Isaac’s “radical shift in our being with God,” he continues, we discover by a kind of interior illumination that “God became human not so much to redeem fallen humanity but simply as a way to show humanity what it means to love.” It is no accident that the word wonder appears numerous times throughout this chapter, both in Isaac’s texts and in Worssam’s careful and loving unspooling of their meanings. There’s a wordless awe—something close to what the author names in a subsequent chapter on the twentieth-century hesychast Saint Porphyrios as “the silence of joy”—at the heart of Isaac’s spirituality, and it is toward this awareness of God’s “infinite creativity” that hesychastic practice tends. As Worssam writes of the hymns of Saint Symeon the New Theologian, poetical renderings of his experience of divine union: “God is the disorientation of the human mind, the loss of boundaries, the silence of concepts, as well as the final, whole, blissful reunion with that which can only be known as love.”

With such heightened language, it can be difficult to remember that hesychasm is not confined to “a mindfulness of consciousness,” but is, at a base, a form of embodied devotion and relational prayer rooted in “the endless invocation of the person of Jesus Christ.” Worssam’s beautiful metaphor of watchfulness as the preparation of the soil and the spontaneous arising of the Jesus Prayer as “the multicolored flowering of the plant” is particularly helpful here. Helpful, too, is his observation that while the Orthodox world has been the primary guardian of hesychastic spirituality throughout history, it is still the common provenance of all the church, West and East, and can thus serve as a vehicle for the unifying, salving, and saving properties contained within the name of Jesus. Moreover, the development of an atmosphere of sanctity around that name, so central to the circulating breathwork of the hesychast, is itself reinforced by our common scriptural heritage (cf. Phil 2:9-10, Acts 4:12, and John 16:23-24, in addition to the biblical origins of the Jesus Prayer in Matt 16:16, Mark 10:47, and Luke 18:13). Worssam’s biography is a witness to this unity: as a member of the Society of Saint Francis, he brings that order’s special charism to his experiential readings of the texts, reminding us at one point that the Franciscans have long held the fourth-century Macarian Homilies in high esteem. In the Stillness, Waiting becomes in the end a testimony to what Porphyrios saw as the participatory mystery of a church modeled on the love of the Trinity: “The important thing is for us to enter into the Church—to unite ourselves with our fellow men, with the joys and sorrows of each and every one, to feel that they are our own, to pray for everyone, to have care for their salvation, to forget about ourselves, to do everything for them just as Christ did for us.” ♦

Michael Centore is the editor of Tomorrow’s American Catholic.