Fearful Clarity

Newsletter for March 7, 2025

Something that has come up quite frequently in our small Christian community these past few weeks has been the notion of praying for one’s enemies. It’s been put forth as a Lenten practice, a way to break down one of the most enduring walls within us: that which erects an illusion of separateness between ourselves and those who would oppose us, that obscures our vision of the truth that no one is saved alone (cf. 2 Pet 3:9).

There is a Byzantine kontakion, or hymn, that confronts this with fearful clarity:

As thy first martyr Stephen prayed to thee for his murderers, O Lord, so we fall before thee and pray: forgive all who hate and maltreat us and let not one of them perish because of us, but all be saved by thy grace, O God the all-bountiful.

We may have a hard time conceiving of our “enemies,” especially if we strive to be at peace with ourselves and with our neighbors. Yet if we dig a little deeper—if we engage in that “shadow work” we see Jesus undertake in the desert in this Sunday’s gospel, facing off against the inner temptation to elevate himself above God—we’ll encounter the myriad petty grievances and judgments, the anger and resentment that still needs to be uprooted if we are to realize those words of Elisabeth Behr-Sigel: “Each one of us is only pardoned and transfigured through the intercession of all and in the communion of the whole church.”

This does not mean a retreat into quietism, a “pernicious peace” that wishes away rather than acts against injustice. For my part, when I use the above kontakion as a prayer, I add the phrase “and your earth” after “maltreat us.” I find that this is where my shadow side is most pronounced: it can be hard for me to humanize those who see creation as a commodity to be bought and sold, who would destroy some of our most cherished public spaces for short-term private gain.

Yet I have to humanize them, and more so I have to include myself within the petition for forgiveness. I live in a country that uses a disproportionate share of the world’s resources, in the part of the world that has most accelerated the effects of climate change. This is the moment when the prayer for one’s enemies expands to become a prayer for humanity. We see ourselves reflected in another’s sin, and we can no longer judge them, but beg for our shared deliverance.

Ash Wednesday, with its elemental symbolism, is an occasion to internalize this. The mark of the ashes represents so many things—our common origin and destiny as dust, the stain of sin that divides us, the cross of our earthly limitations—and wearing them helps call to mind our frailty and our faults. It humbles us to think that we might be on the receiving end of a prayer for one’s enemies, that someone whose life or country has been endangered by our behavior might be including us in their petition.

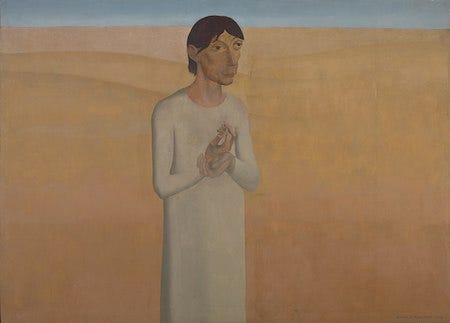

Lent is a time to live with this insight, to carry it forward in repentance. I keep returning to the image of the desert as a perfect correlative. In this “solace of a fierce landscape,” to adapt a title from Belden Lane, we are brought up against ourselves and all of our self-evasions. The harshness of the light clarifies and purifies. What at first seems unforgiving becomes the ideal setting to practice forgiveness: a place where everything stands revealed and we are forced to accept our utter dependence on God.

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic