Jesus and Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion by Charlie Gibson

Jesus came on this earth to establish the kingdom of God—in modern-day parlance, the “community” of God. This is what he proclaimed at his synagogue in Nazareth: “The spirit of the Lord has been given me, for he has anointed me. He has sent me to bring good news to the poor, to proclaim liberty to captives and to the blind new sight, to set the down-trodden free, to proclaim the Lord’s year of favor” (Luke 4:18).

To heal and cure, to free, to provide hope and freedom for the oppressed: this was proclaimed in an environment that was religiously and politically oppressive. In addition to this “assignment,” Jesus said his “program” had two principal requirements. The first: “You must love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all soul and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment” (Matt 22:37-38). The second resembles it: “You must love your neighbor as yourself” (Matt 22:39). So strong was this second great commandment, in fact, that the evangelist John says that “Those who say, ‘I love God,’ and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars (1 John 4:20).

And who is my neighbor? Jesus says it is every person (cf. Luke 10:29-37). To drive this home, he tells the parable of the Good Samaritan. There was great enmity between the Samaritans, who were fundamentally Jewish but believed that God wanted worship confined to Mount Gerazim, and the Jews who were primarily in Judea and believed that God wanted worship confined to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. In Jesus’s parable, the demonized Samaritan who takes care of a stranger who has fallen in with robbers and been left for dead shows more compassion than two Jewish religious leaders who pass by the victim because they would be considered impure if they touched blood, and thereby could not function in religious ceremonies. Jesus emphatically points out that charity and compassion trump religious rules.

What made Jesus so attractive to ordinary people, along with his ability to cure many physical and mental ills, was that he “walked his talk.” This means that he showed not only by words but also by his behavior that he advocated and manifested diversity, equality, and inclusion.

Diversity

Jesus welcomed all types of people, especially those who were social outcasts, oppressed and worn down by the political and religious system. One did not have to be Jewish to enter into the orbit of his compassion. Examples include the woman who was an adulteress (John 8:3-11); the Samaritan woman (John 4:1-42); and the cure of two pagans, the daughter of the Syro-Phoenician woman (Mark 7:24-30) and the servant of the Roman centurion (Luke 7:1-10). Additionally, among Jesus’s twelve closest followers, the apostles, there were at least four fishermen (Peter, Andrew, James, and John), a tax collector (Levi), a “zealot” or terrorist (Simon), and a traitor (Judas).

Equality

Jesus treated all with equal dignity. He had a special affection for the poor and oppressed and scathing criticism for religious leaders, many of whom had contempt of people not as religious or knowledgeable of the Law as they were.

These leaders were seeking reasons and justification for getting rid of Jesus. They used police (hypēretai) to gather evidence to eliminate him, but the police returned instead with admiration for what he taught and did. The leaders’ response was, “This rabble knows nothing about the Law—they are damned” (John 7:45-49). Such ignorant people were considered spiritually inferior. Nicodemus, also a religious leader, stated, “the Law does not allow us to pass judgment on a man without giving him a hearing and discovering what he is about.” The other religious leaders retorted Jesus did not have the proper “papers,” that is, their Scriptures did not say any prophet came out of Galilee (John 7:42-53).

Where the “purity laws” which held certain people—for example, “lepers” or women experiencing menstruation—as ritually unclean and to be avoided, what was important for Jesus was to be clean inside. Religious rules were secondary to taking care of people who were suffering or in difficult circumstances.

What was radically different in Jewish Palestine was how Jesus treated women as equals. Palestinian women had the lowest status of women in the Roman Empire. They could not initiate divorce or own property, and it took two women to take the place of one man in giving witness. A woman was the property of her father until married, and then became the property of the husband. Women, especially married women, were to be chaperoned by their husband or a member of the husband’s family and were not to talk with another man. But Jesus considered women equally competent to engage in spiritual and religious conversation, even though their “chaperone” was not present—for example, with Mary Magdalene (Luke 10:38-42) and the aforementioned Samaritan woman (John 4:1-42).

Where Jesus really broke the taboo was having a group of women who traveled with him (along with the 12 closest disciples): Mary Magdalene, Joanna (the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza), Susanna, and several others (Luke 8:1-3). These women had been cured of physical and spiritual maladies by Jesus and had access to financial resources.

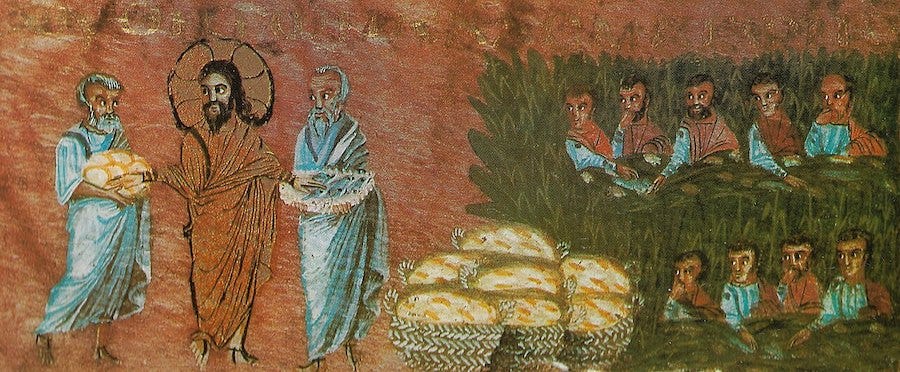

Inclusion

In this area Jesus also upset the social order. He would converse and eat meals with those whom self-righteous people would shun. He ate with “sinners” such as prostitutes, tax collectors, people who were considered unclean. Again, he accepted women as equals.

Jesus held personally that whatever one did to the least of his sisters and brothers was done to him. One who was truly holy and righteous was one who fed the hungry, gave drink to the thirsty, welcomed the stranger, clothed the naked, and visited the sick and imprisoned. On the other hand, he chastised those who neglected or refused to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked, and visit the sick or imprisoned as not worthy of the kingdom of God, since “whatever you neglected to do this to one of the least of these you neglected to do it to me” (Matt 27:31-46).

Another issue that shocked even his dedicated followers was Jesus’s comment on the moral danger of riches. “It will be hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven . . . it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 19:16-26). This is one of the “hard sayings” of Jesus. His comment is based on the fact that in many cases people with wealth can “buy” the support of politicians who make and administer laws and then have laws enacted to further increases their wealth and influence at the expense of the population at large, especially the most economically venerable. The “system” is “rigged” to primarily support the most well-to-do. ♦

Charlie Gibson serves on the steering committee of Catholic Church Reform International.