Poetry and the Trinity

A reflection for the Sunday of the Word of God.

I like to think of the Trinity as a poem: the Father is the author, the Son is the text, the Spirit is the sound, the meaning, the resonance. In the Nicene Creed, we proclaim:

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son,

who with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified,

who has spoken through the prophets.

The phrase “and the Son” is known as the filioque. It was not present in the original Creed and only inserted by the Spanish church at the Council of Toledo in 589. Its use spread through Western Europe, but it was never accepted by the Eastern churches and was one of the reasons for the Great Schism of 1054.

I confess to a certain ambivalence about the filioque. I repeat it week after week, though when I come to that point in the Creed part of me always wonders if I am intoning an extra note that deviates from the harmonious melody of the Trinity. As Jesus himself teaches, “When the Advocate comes whom I will send you from the Father, the Spirit of truth that proceeds from the Father, he will testify to me” (John 15:26).

At the same time, I can understand the Western perspective, codified in the Council of Florence in 1439, that affirms the filioque and the notion of the Spirit proceeding also from the historical mission of the Son. I envision it as a trail of light, of inspiration, that issues from the Son even as it pulls him along on his journey. It is the source of his self-awareness that intuits his next step and creates the conditions for each corresponding action. It both awakens his knowledge of oneness with his Father and enkindles a desire to open up that path of oneness to others, a vocation realized with such fidelity to the Spirit that each healing, each teaching, each dispatch bears traces of its breath. Much as the life of the Son is eternally present in the Father, so is the generation of the Spirit eternally present in the Son.

Compare this to the life of the poem. The poet is not, technically, her poem, yet at the same time her essence permeates every word of the text. The more she has done this, paradoxically—the more she has concentrated (I almost wrote “consecrated”) herself into language—the less “personal” the poem becomes, the wider its scope of potential meanings, readings, subjects, and encounters. This is cousin to the ageless literary insight that the universal is achieved through the local, something we watch Karl Ove Knausgaard rediscover in the sixth volume of his autobiographical novel My Struggle:

Back then I hadn’t understood the value of the iconic, it was too alien to me, nothing in my life and writing coalesced to form an image, everything overflowed its banks. Now I understand. The iconic is the pinnacle of literature, its real aim, which it is constantly striving to achieve, the one image that contains everything within but still lives in its own right. . . . All literature wants to go there, to the one essential symbol that says everything and is at the same time everything.

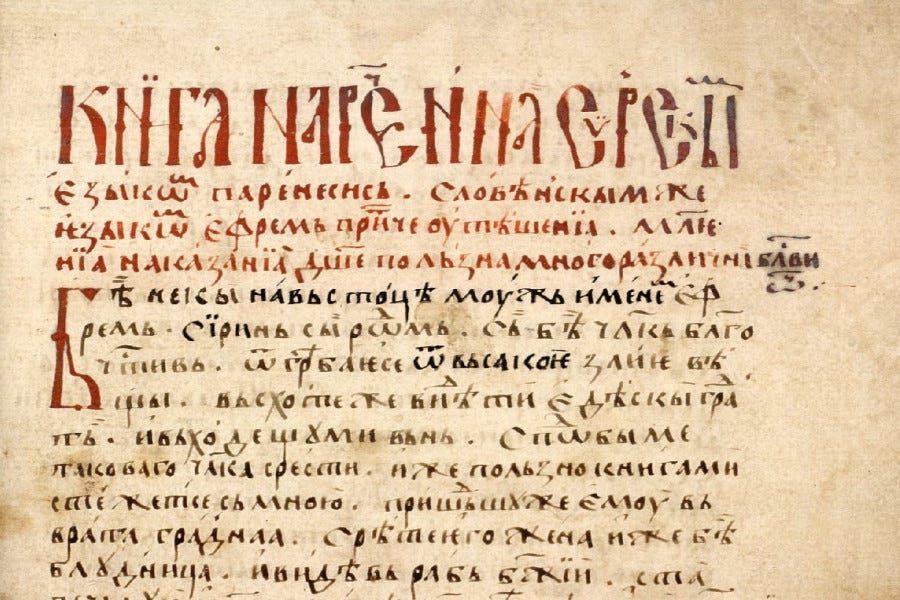

Robert Frost writes somewhere of his admiration for Thoreau’s genius in having distilled his life to one image—to one word, even—being Walden. To think of a person distilling a life to a word has special import on this Sunday of the Word of God, proclaimed by Pope Francis in 2019 with the apostolic letter Aperuit Illis. Francis opens with a quote from Saint Ephrem the Syrian, a poet who understood that liturgical and homiletical expressions of faith must aspire to poetry’s condition of pure possibility:

Who is able to understand, Lord, all the richness of even one of your words? There is more that eludes us than what we can understand. We are like the thirsty drinking from a fountain. Your word has as many aspects as the perspectives of those who study it. The Lord has coloured his word with diverse beauties, so that those who study it can contemplate what stirs them. He has hidden in his word all treasures, so that each of us may find a richness in what he or she contemplates. (2)

“God lives where faith and love become song,” wrote Francis’s predecessor Benedict XVI. Aperuit Illis continues, “We can say that the incarnation of the eternal Word gives shape and meaning to the relationship between God’s word and our human language, in all its historical and cultural contingency” (11). The “meaning” of the Word, its theophany, is a poetic revelation, much in the way we come to know the poet through her images, stresses, selections, and cadences: the lineaments of a face in text, which we behold in the icon of the page. The agent of this revelation is the Spirit, present in us as it is present in the Father and the Son, the poet and the poem, and whose self-disclosure only requires our willingness to listen after Saint John of the Cross: “The Father spoke one Word, which was his Son, and this Word he speaks always in eternal silence, and in silence must it be heard by the soul.” ♦

Michael Centore

Editor, Tomorrow’s American Catholic

Wow, a lot to reflect on. Thanks, Michael , we'll done.