The Life of the Dreamer and the Dream of the Church

Newsletter for April 11, 2025

The final session of our Lenten Synodal Practice earlier this week was devoted to part V of the Final Document, “So I Send You.” The subject of the section is formation—the ways in which people are “molded” to Christ and, within this process, come to know themselves as carriers of their own unique gifts and charisms that can then be passed on to others.

Our group thought through the many different modes and challenges of formation. One participant spoke of a need for a new theology of missiology in a postcolonial world; another cited the major shift in thinking of laypeople as “subjects” and not just “objects” of formation; a third asked us to consider “the need of the hour” and played upon the relationship between what should be conformed, reformed, and transformed in the work of formation.

One thing that impressed me throughout our exchange was how many times religious formation was linked to our formation as “global citizens,” with the church as a “global dialogue partner.” This is to say that formation is not just a self-enclosed system of rites and processes, but a way of bridging out to the world. It means recognizing where the church has fallen short by aligning itself with imperial power above the needs of “the least of these,” and shaping missionary disciples who are prepared to do the spiritual work of atonement alongside the corporeal works of mercy.

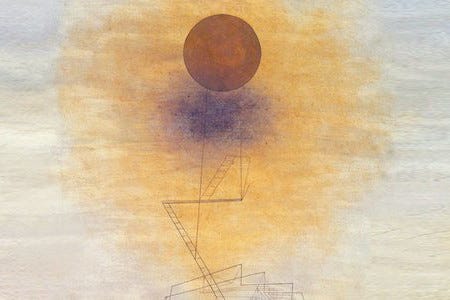

As formation bridges out, so can it reach down to the left behind, the marginalized, the one who needs an outstretched hand. And there is still another way to think of this descent: as a reaching down into consciousness itself, to re-form and re-connect ourselves to the trove of deep images and symbols that has attenuated over time.

In her essay “The Process of Individuation,” the Swiss Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz speaks of the “uprooted consciousness” of postindustrial humanity, cut off as we are from what Jung terms “the Self”: “an inner guiding factor that is different from the conscious personality and that can be grasped only through the investigation of one’s own dreams.” The Self is both the “totality” and “nucleus” of the psyche, where we are bonded to all creation through the inner logic of the unconscious mind. Such a connection manifests itself most readily in our dream life, with its access to a sea of archetypal images supplied by our earliest forbears and replenished over time.

Should not part of our religious formation, then, be to “re-root” our uprooted consciousness in the fertile soil of the Self? After all, it is one of the great gifts of the world’s religions, and of the church more specifically, that they maintain our connection to the rhythms of ritual, nature, lament, and praise.

Next week the church enters a season of profound symbolic import: the death and resurrection of the cross, the eternal drama of suffering and redemption. We lose that depth when we turn Christ into a cipher for “morals” or “ethics”—or, worse yet, when we use him as a tool to prop up the agendas of wealth, dominance, and exclusion. By way of illustration as to how all of this relates to the life of the dreamer and the dream of the church, here is an example from one of von Franz’s analysands:

Another Catholic woman, who had resistances to some of the minor and outer aspects of her creed, dreamed that the church of her home city had been pulled down and rebuilt, but that the tabernacle with the consecrated host and the statue of the Virgin Mary were to be transferred from the old to the new church. The dream showed her that some of the man-made aspects of her religion needed renewal, but that its basic symbols—God’s having become Man, and the Great Mother, the Virgin Mary—would survive the change.

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic