Thoreau’s Avatar

Further excerpts from a work in progress.

I’ve come to the Connecticut River as I always do, in search of something, I don’t know what. I’m young—sixteen, I’ve just received my driver’s license this past spring. The driver’s license is a function of the suburbs; it is a passport to anything of interest, to this river, for instance, or the game preserve with its network of trails and old tote roads that I frequent on the weekends. You cannot walk to such places from where I live without passing first through miles of strip malls and subdivisions, and this is a key difference between the twentieth century in which I am coming of age and the nimbus of the nineteenth in which I mean to lose myself like a contemplative in his cloud. I am one for whom going out “into nature” is like going to the store: another errand, albeit a soul’s errand, fitted into the pattern of works and days as one might pick up his dry cleaning.

Contrast this with the two lodestars whose work I carry with me in my rucksack, and certainly had with me that day, Emerson and Thoreau. For the former it was a five-by-four-inch edition of “Nature” published on occasion of Penguin’s sixtieth anniversary and sold at the bargain-basement price of ninety-five cents; for the latter, the Bantam Classics edition of Walden and Other Writings with its cover of bands of November-leaf brown framing a painting of what can only be termed a countryman aristocrat: his posture erect, almost haughtily so, he stands with his right foot in front of his left, as if he has just caught himself up after cresting a hill. His hands rest atop a walking stick that parallels the ramrod-straight posture; he wears a gray blazer and a hat in the alpine style. An external-frame knapsack, its squared-off shell resembling a valise, is slung over his shoulders. His bearded face is shown in profile, though we cannot see his eyes: he is turned away from us, contemplating an autumnal hillside in russet reds and greens.

The first thing I imagine about this solitary walker and avatar of Thoreau is that, upon leaving his home that morning, he did not need to pass through a zone of excess to arrive at a zone of simplicity. He lit out for a day’s walk; immediately he was “in nature.” The divide between nature and culture was not so firmly established. There was no need to “get away from it all”; “it all,” for him, was the grand totality of the cosmos from which he could not escape even if he wanted to, whereas “it all,” for us, has come to represent the sum slag of modern life, the million myriad transactions we place between ourselves and true encounter. When the notion of “it all” becomes so disfigured, we lose our place in the universe; our minds that were once like flames, striving upward in their verticality, now peter out into the low, slow burn of raked embers being extinguished by the rain. We lose our sense of wonder, of awe—and what’s more, we don’t realize we’ve lost them, or that they were even ever ours to lose. The world pulls us back at every turn. It suffocates us, it blinds us and deals us blows. Even the tree can be ironized: we see it there in the supermarket parking lot, we know it has been purposefully planted because, as the arborist tells us it thrives in shady environments, this great plain of sunbaked asphalt will ensure it doesn’t grow too tall and ramify roots that buckle and crack the pavement. We sacrifice the producer of life-giving oxygen for the sake of the suspension of the vehicle that emits life-smothering carbon dioxide. Meanwhile the tree subsists as a figment of the forest’s imagination, as isolated as a fossil preserved in stone, as fragmentary as regards creation as a line from Heraclitus pulled out of context and inserted at random into a supermarket tabloid. We catch ourselves thinking it would be better off if it wasn’t even there, planted so unlovingly, mocked and scourged by the surrounding strip mall’s jeering ugliness.

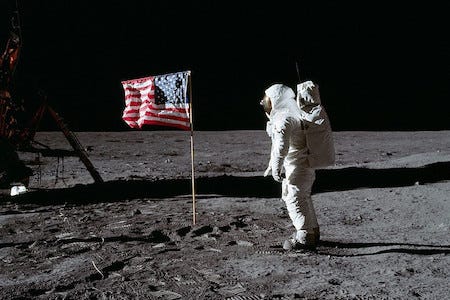

The second thing I imagine about the solitary walker is the contents of his knapsack. I see volumes of Greek poetry and Hindu philosophy, Virgil’s Georgics and the Rig Veda, their lines carrying him along in shady glens and atop the cool fastnesses of boulders. Though he be multiple millennia and many thousands of miles removed from the sources of these texts, I speculate that he felt closer to the natural imagery they employed in 1850 than I did to Thoreau’s natural imagery in 1996—that their themes of birth, death, decay, and rebirth, as modulated across the living symphony of the landscape through the keys of its animal, vegetable, and mineral life, resonated with greater richness and precision within his inner ear, dwelt with a more electric innateness within the fiber of his inner being than they did within my own. To put it another way: my solitary walker had less of a distance to travel to reach with understanding the ancient Greek poet or Hindu hymnographer than I did to reach the comparatively current Thoreau; their declamations rested on agrarian rhythms that the walker would have recognized, mutatis mutandis, as part of his experience of the regulation of time, whereas I, upon my first reading of Walden at sixteen, had yet to even encounter that image of fecundity so central to the text, the bean-patch, in its natural state. Put yet another way, in the language of the pithy aphorism that is not unrelated: George Washington and Julius Caesar traveled at the same speed, and it was not until the incursion of the railroad, that bane of Thoreau’s existence, that humans began to bend and shape their relationship to space and time. They no longer rode on horseback, but on horses bred of iron, and thus began a rapid outstripping of thousands of years of lifeways and a drastic, if not to say violent breaking away of the human from the established pace of his actions, perceptions, and motilities. He could never escape, no matter how many railways, then highways, then skyways he wrapped the earth with, no matter how fast he traveled over them or how laudable, from the perspective of human ingenuity, that pièce de résistance of aspirational self-assertion: his storming of Tranquility Base as though it were another Bastille and he a republican protesting the moon’s monarchical control over the tides.

In a way these complaints belong to the twentieth century; they have no more real purchase here in the twenty-first other than as rhetorical devices to set up a conversation about the nature and limits of “progress.” We have outgrown them, or rather internalized them to such an extent that they no longer need to be repeated. Those of us who straddle the two centuries—at the time of this writing, I have lived a symmetrical twenty years in each—have begun to ask ourselves: What is the railroad today? What is the machine, and in what garden? One friend says Amazon’s corporate consolidation of goods and services, its tentacle-like reach into spaces previously consigned to the public trust;[*] another says genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, including the patenting and ownership of seeds by multinationals; a third says no, it is surveillance capitalism—it is the tools of the internet harnessed to turn users into products—it is the camera in the laptop that you authorized the website to access so that you and I could see each other’s face as we spoke remotely about the danger of authorizing websites to access the cameras in our laptops so that we can see each other’s face as we speak remotely, thereby taking our place in the feedback loop of modern life in which we are at once watcher and watched, spy and spied-upon. This feedback loop is really more of a Mobius strip in that it appears to have two sides but really only has one, the screen that is our interface, that turns what we consume into what we create; we go around and around in circles with the Mobius’s twist in the middle tricking us into thinking we have experienced duality, a dialogue, when all along we have been left with only ourselves. This is why people on the internet talk endlessly about the problems of the internet: its cyclical structure, its “Mobiusness,” so to speak, narrows the perspective necessary to solve its most egregious problems: its extension of the surveillance state, but also its hazards of dehumanization and social fragmentation. The more we depend on it to bring us together, the more it drives us apart. The more it drives us apart, the more insolvable it becomes. The more insolvable it becomes, the more we are entangled in its laws and legalese, its end-user agreements that are the representative texts of our time, the further we are insulated from the language of vision and prophecy. Lacking this language, we are content to become diagnosticians. If we cannot articulate the solution, we say, we can at least articulate the problem. And there are as many problems as there are people trying to name them, because in this age of algorithms and metrics and data points that collect about us and reconstitute the saleable parts of our psychospiritual lives as flickers of light in glass, even the ways we conceive of our social sickness are hyper-individualized.

When Thoreau singled out his railroad breaching his idyll at Walden from a third of a mile away, he knew precisely what he was referring to. Our age is not so simple. We have railroads coming at us from all directions, infiltrating our lives down to the level of domestic space like the locomotive emerging from the fireplace in Magritte’s Time Transfixed. Thoreau’s “cloud-compeller”—his term for the steam-spewing engine—is our cloud computer, breaking information to bits and scattering it throughout the atmosphere. It is no wonder we experience information as precipitation constantly raining down on us, or as fog constantly obscuring. This is borne out by the way people speak: note the next time you hear the phrase “I feel” in place of “I know,” “I believe,” “I understand,” or “I think” to signal asseveration, and it will soon become apparent how we are all groping our way through the daily media miasma to state the most basic facts. This only complicates the naming of our railroads—which, again, are as numerous as there are interior idylls to disrupt, and which seem designed to abstract us from ourselves—and leaves us with the prevalent feeling of our historical moment: the interconnectedness of everything breaking down, and our powerlessness in the face of such an overwhelming systemic collapse. At the same time, we have never been more aware; the media miasma has fostered a period of peak opinion in which everyone has something to say about everything always even as it has occluded our perceptual powers of the kind nurtured in contemplation and reflection. We know there is something wrong, and yet the minute we label one problem, three more have sprung up in its place. We spend more time labeling than we do solving. Our age is a veritable taxonomy of despair. In such an environment, where can we hope to find the solid ground from which to act? Amidst the shifting sea of uncertainties—a sea which, like all the seas of our century, is rising to swallow bastions held to be secure—how do we find a foothold that we might still our tireless tongues and begin to engage our hands?

I return here to my place on the river—the east bank, just south of the Enfield Rapids. Charles Dickens would have sailed right by this spot on his way from Springfield to Hartford in 1842, a trip he later wrote about in his American Notes. That same year, some hundred miles to the northeast in Concord, Thoreau was living with the Emerson family in the capacity of handyman and tutor to Emerson’s children: I seem to recall an account of Thoreau making popcorn in the fireplace with his young charges, a moment of tender domestic intimacy that softens our portrait of that often irascible naturalist. As I peer back through the lens of memory, I like to imagine the closed flap of the rucksack at my feet as the roof of the Emerson household, the souls of the two men in their textual forms holding converse in 1996 the way they might have in the flesh a century and a half before. I see myself on the river’s edge, seeking their inner heat, trying to take up their transcendentalist project with all the limitations of my inexperience and the impositions of my time. Their texts are not so much philosophical tracts as metaphysical maps of a noetic terrain, which I will consult with greater frequency than any trail guide to keep myself properly oriented:

But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars.

I watch. I wait. If I only knew how much these two postures, watching and waiting, would come to figure into my life, such as that they are essentially my adult occupation—I am a watcher, a waiter, I hold myself in a place of active expectation that is, I see now in typing the phrase, cousin to Kierkegaard’s “armed neutrality.” But those self-discoveries are still to come. The July sun burns hot and bright. The air is thick with humidity, barely cooled by the breeze off the river. There are train tracks behind me, but I am not aware of them; unlike Thoreau, I have grown accustomed to metal lines lacing the landscape and the metallic sounds of whistles and wheels as they sing shrilly or grind along the rails. I am not looking behind me, but ahead, upward, my sightline rising on the oblique to take in, then land on, the two circling birds. And I stay with them. I stay with them with a strange focus such as I have never known, as if their flight were accomplishing this focus within me. They seem to exist for no other reason than to instill this focus. For a moment I lose consciousness of everything except their movement and my apprehension of it, and then their movement overtakes my apprehension so there is nothing left to be conscious of. There is just the movement of life experienced in absolute stillness. They wheel and they level and they recalibrate and they point their way northwest and flap their wings and drive off into the sky and I am standing on the bank and this moment of movement wherein my earthbound heart and the birds’ airborne beat beyond together, beat within a shared sustaining rhythm that animates the planet and removes, in the final analysis, so many of the barriers we impose between species—this moment already begins to leave its residue of words within me, and they thrum with the truth of some primordial understanding: We share the earth.

[*] To this I would add the insidious way that retail behemoth’s name now contests with that of the South American river in our collective imagination. When all is said and done, when the trinkets and doohickeys have all been delivered and the drones melted into ploughshares, this may be its most lasting legacy.

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic