Trakl's Colors

Red coins, yellow fields, green torrents, purple dreams, white water, grey silence.

Let us consider the colors of the German Expressionist poet Georg Trakl (1887–1914). Here are a few examples taken at random:

There is a stubble field on which a black rain falls.

(“De Profundis”)

Evenings on the terrace we got drunk with brown wine.

(“Helian”)

A blue deer

Bleeds in the thorny thicket quietly.(“Elis”)

There are many more, almost (at least) one per poem, covering the whole spectrum of the rainbow: red coins, yellow fields, green torrents, purple dreams, white water, grey silence. There is the silver face of a friend and the last gold of a perished star.

In a way Trakl reminds me of Bonnard, not in tone but in approach. Bonnard who, as James Elliott tells us, “seldom recorded acts or events. His concern was with the feelings—the ‘poetry’ as he called it—evoked by the things he knew best.”

To evoke is the concern of poetry. What Bonnard did in paint, Trakl does in words: he locates the object keyed to a particular emotion and assigns it its proper hue. Thus the “brown wine,” though it comes amid images that speak of summer, seems to contain a foretaste of autumn, November’s umber leaflitter that crumbles the way alcohol in excess does an evening or a person.

There is a story of Bonnard acquiring a Renault and making his first road trip to Mont Saint-Michel. He used to drive slowly through the countryside, stopping here and there wherever the spirit moved him, sometimes staying overnight at little wayside inns. I like to imagine him on the edge of some paysage, taking in the colors of the landscape. I am interested in this moment of contemplation prior to composition, when he lets the shades and tones of tree, earth, and sky refine themselves through his emotions. The painting is far off—so far it may never be painted. In the intervening time the sun will become more scarlet, the leaf more aquamarine.

I don’t think Trakl had this luxury of time. His life feels too rushed, too frenzied—war, death, wine, cocaine—for sustained contemplation. Yet the rhythms of his colors and images instill in us a profound quiescence, almost a reverence, even if it is the silence of a heart brought to the fullest pitch of intensity:

Unspeakable it all is, O God, one is overwhelmed and falls on one’s knees.

(“Wayfaring”)

Color is the quickest way from the eye to the soul. This is not limited to poetry or painting. The pianist András Schiff identifies each of the keys in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier with a chromatic equivalent, from the snow-white of C major to the pitch-black of B minor and all points in between:

first the yellows, or oranges and ochre (between C minor and D minor), all the shades of blue (E-flat major to E minor), the greens (F major to G minor), pinks and reds (A-flat major to A minor), browns (B-flat major and B-flat minor), grey (B major) . . .

When Rousseau arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1741, one of the first people he met was a Jesuit priest named Father Castel. Castel had invented something called the “color keyboard”—according to a footnote in my edition of the Confessions, “an instrument for producing color harmonies; the primary colors, corresponding to the seven notes of the scale, were projected by the notes of a keyboard similar to that of a harpsichord.”

Trakl plays his colors like Castel the keyboardist or Schiff the clavier whisperer. They are descriptors of an inner essence of a thing, be it a fountain or a smile or a season. But more than this, they cast their glow over the entire poem. One yellow wall of summer changes an entire stanza, so that when the red wall of autumn appears several lines later, we grasp, in a vision quicker than syntax, the passing of the year.

Trakl’s great trick, commented upon by other critics, is this perfect marriage of syntax and image. Like the mysterious source of the stillness it engenders within us, we are never quite sure what is propelling the poem. It is not the temporal march of narrative, though there is something like sequential events related with a hushed omniscience:

Gladness, when in cool rooms a sonata sounded at nightfall,

Among dark-brown beams

A blue butterfly crept from its silver chrysalis.(“Sebastian in Dream”)

We are not sure where the sonata might fall on Castel or Schiff’s spectra, but my intuition is the green of G minor. The dark-brown of the beams encloses us, the blue of the butterfly sets us free. We emerge from the silver of the chrysalis into another poem, one that apotheosizes our experience of Trakl’s grammar of the senses:

A blue moment is purely and simply soul.

(“Childhood”)

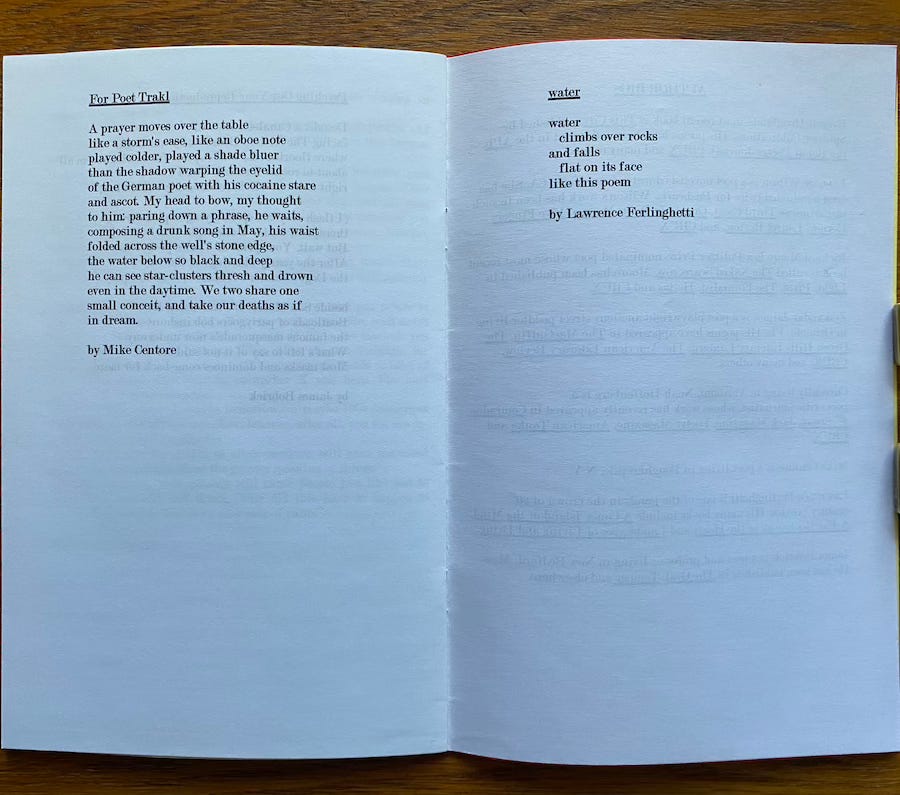

Michael Centore

Editor, Today’s American Catholic